Project: Concept study & design of a life raft for refugees in distress at sea

Concept: Michael Grausam, Andrea Bitter

Design: Michael Grausam

Period: Development 2008

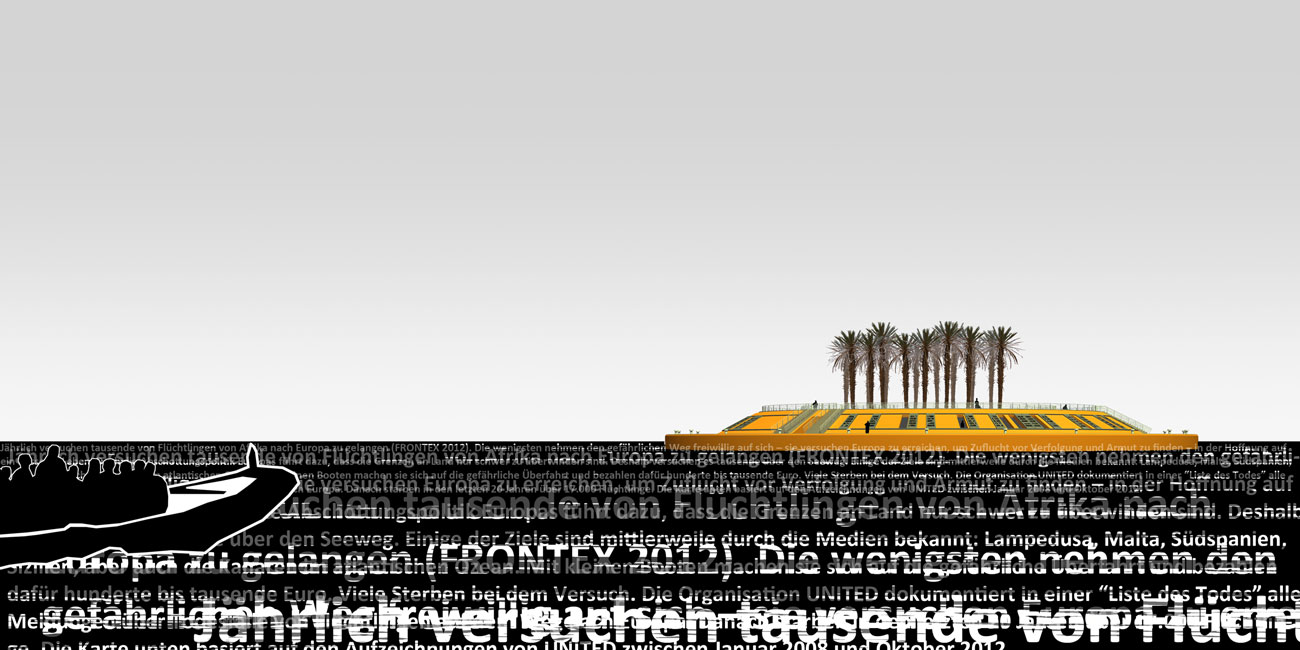

Every year, thousands of refugees try to reach Europe from Africa (FRONTEX 2012). Very few of them take the dangerous journey voluntarily – they try to reach Europe to find refuge from persecution and poverty in the hope of a better life. However, Europe’s isolationist policy means that the borders on land are difficult to cross. That is why thousands are trying to cross by sea. Some of the destinations are now well known in the media: Lampedusa, Malta, southern Spain, Sicily, but also the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean. They make the dangerous crossing in small boats, paying hundreds to thousands of euros. Many die in the attempt. The organization UNITED documents all reports of deaths of refugees on their way to Europe in a “list of deaths” According to this list, over 17,000 refugees have died in the last 20 years.

Causes of death include drowning, dying of thirst, starvation and freezing to death. These are not always accidents. Sometimes people are thrown overboard when border patrols approach or the boat gets into difficulties and weight has to be reduced. There are traffickers who are more afraid of being caught than they have scruples about killing a person. Help is not always given when a refugee boat is in distress at sea. Captains who pick up refugees and bring them to safety on the European mainland are often accused of being traffickers. One particularly prominent case was the accusation against the captain of the Cap Anamur, Stefan Schmidt. He had picked up refugees in distress at sea and had to sail along the Italian coast for weeks in search of a port that would let him enter. He finally entered the port of Empedocle without permission, whereupon his ship was confiscated and he was put on trial. After five years of trial, he was finally acquitted. But few people have the courage and money for such a long and costly trial.

According to international maritime law, people in distress at sea must be helped. Nevertheless, there are repeated reports of captains who do not take refugees in distress on board and leave them at sea. This makes them guilty of failing to provide assistance. On the other hand, many fishermen’s livelihoods are at stake if they are accused of smuggling by the authorities or are unable to enter port to unload their cargo. The situation is therefore paradoxical for the captains in two respects: if they help, they are criminalized; if they do not help, they are guilty of failing to provide assistance and have to carry the guilt with them for the rest of their lives.

Why is Europe doing nothing about this deplorable state of affairs? In the face of this unresolved humanitarian catastrophe, the otherwise high European values seem to be finding their grave together with the drowned refugees in the Mediterranean. Instead of massively stepping up sea rescues, supporting civilian rescuers and actively combating the causes of the refugee movement, the FRONTEX border defense is being expanded, the fences in Ceuta and Melilla are being raised and Fortress Europe is being further sealed off. Officially, Europe is committed to accepting refugees seeking refuge from political persecution, civil war or other threats to their physical integrity. Anyone who has set foot on European soil can apply for asylum. In reality, however, European states try to keep refugees off their soil. Although Italy launched the military operation “Mare Nostrum” in October 2013 in response to public pressure with the aim of rescuing refugees, the controversial Bossi-Fini law remains in place, on the basis of which anyone who takes refugees on board off the coast of Italy can be accused of smuggling (Süddeutsche, Oktober 2013).

In view of the many crises in the world, it may seem understandable that Europe is afraid of the masses of people who would at least be entitled to an asylum procedure under the above-mentioned aspects. It would therefore appear that the situation cannot be resolved in this way: if Europe stands by its values, it must expect to be overrun by refugees; if Europe does nothing about this deplorable state of affairs, it betrays its high humanitarian ideals and values.

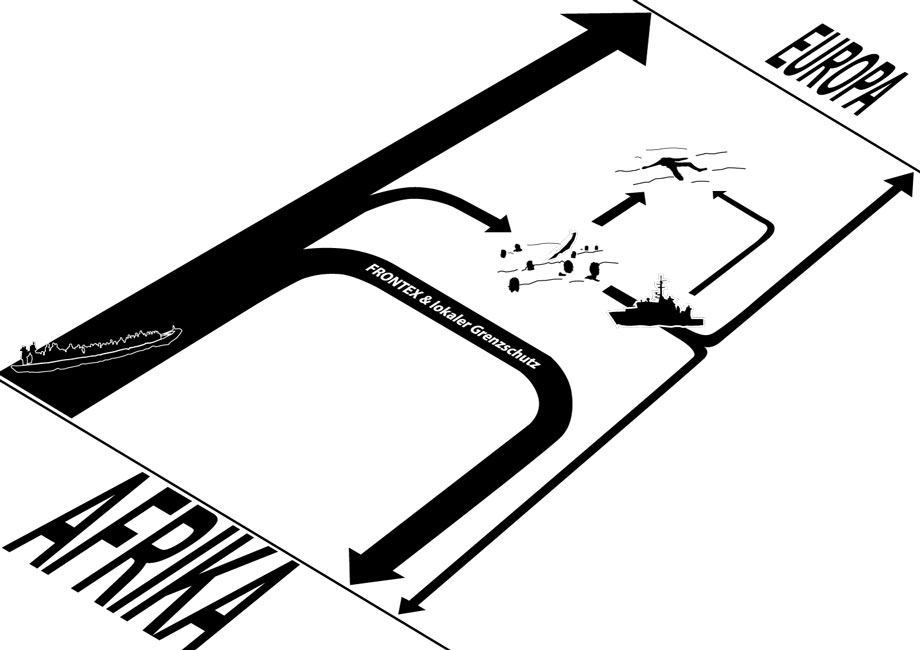

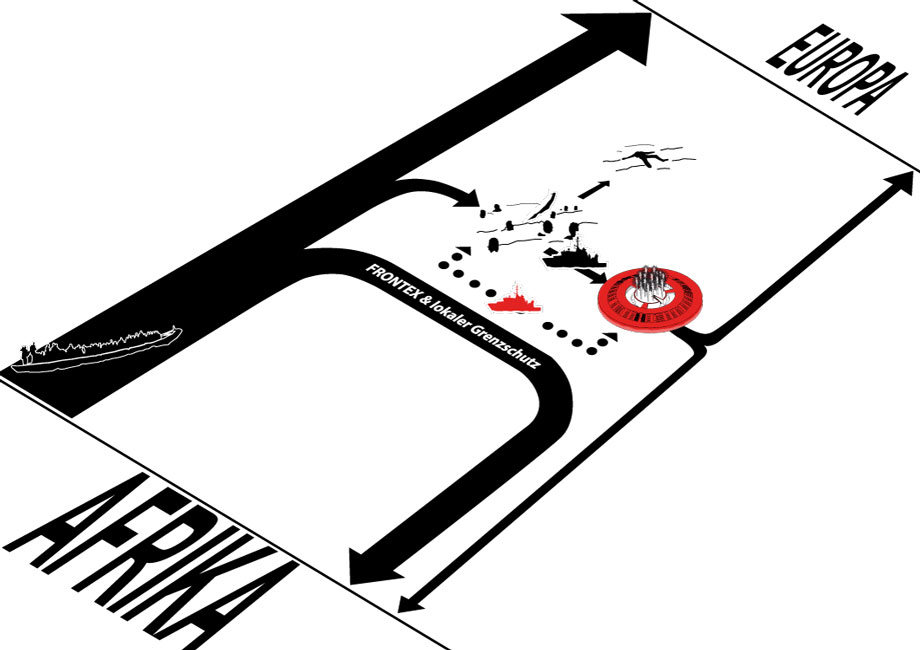

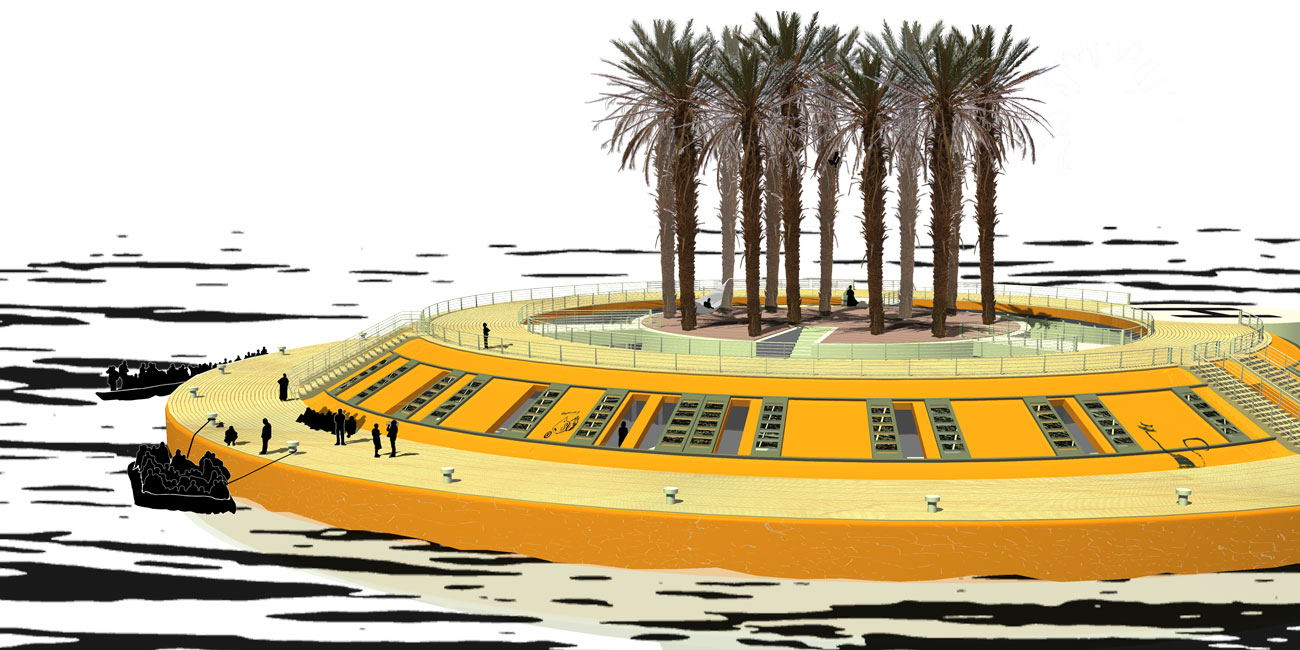

How can we manage to untie this Gordian knot and enable civilian rescuers and captains to help refugees in distress at sea without being criminalized for doing so? At the moment, no European state seems willing to accept refugees unconditionally. The third country regulation shifts this pan-European problem onto the southern European states alone. These states, in turn, are trying with all the means at their disposal to keep the refugees away from their national territory. Do we need neutral ground between Europe and Africa, an island of humanity where people can be helped without ifs and buts? In other words, a life raft in international waters where captains can deliver rescued refugees without fear of being punished – a “baby hatch for refugees”, so to speak? This would at least provide a way out of the humanitarian catastrophe of looking the other way. However, this approach must not obscure the fact that the causes of the refugee movement must be eliminated at the same time and the examination of asylum applications in the respective home countries must be made possible.

Sea Shelter concept

An artificial island in international waters and therefore outside of national territory would meet the requirement for neutrality of humanitarian aid. Under the flag of the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), refugees in distress at sea could be brought to the life raft, the offshore shelter, and initially receive medical care. Captains would not be criminalized for their help. The Mediterranean Sea between Tunisia, Libya, Lampedusa and Malta would initially be a suitable location. This is where most refugee boats have capsized in recent years and the sea shelter could serve as a base for rescue operations in the region.